What is a football match for a mathematician? The answer is: ‘A single division of a unit interval into two equal sets’. But for sports fans, it’s a lot more: it’s a heroic fight until the end. How do we compare these seemingly irreconcilable frames of mind?

In his book Soccermatics: Mathematical Adventures in the Beautiful Game, David Sumpter, a professor at Uppsala University specialising in Applied Mathematics, tries to find an answer to this question. When we look at football from the mathematical perspective, it becomes easier to understand, but more importantly, it also becomes easier to appreciate its beauty.

Mathematics has always been a part of football. In the beginning, it was just the statistics. However, as time went on, computers began to analyse every minute detail of every important match, processing the number of goals, passes, interceptions, and saves. All of that computing power is put to use in the training centres of major football clubs. As much as nutritionists, physical therapists, and psychologists, analysts have become important members of football clubs’ staff. Their primary objective? To identify and exploit the opponent’s weaknesses while min-maxing their own team's strong and weak points.

Unpredictability

Someone could now say that it’s impossible to predict absolutely everything in football. Probability theory and other mathematical tools can make football matches clearer to us, but surely we can’t do away with luck and human factor when we discuss sports, can we? Perhaps football’s greatest appeal is its unpredictability. If not for that, how could we explain the fact Iceland managed to get a tie with Argentina led by Lionel Messi during the 2018 World Cup in Russia? All things considered, everyone was sure that Argentinians would've have crushed the descendants of Vikings in nine games out of ten. How can we navigate by logic and order in the world of sports – a tempestuous sea of chaos, particularly to inexperienced viewers?

David Sumpter talks about mathematical models. He compares the ones he finds in nature, mathematical theory, and on the football pitch. On notable example is networking. It's clearly visible in the case of the Tokyo subway system.

Japanese urban planners did a good job in designing its infrastructure. How do we know this? Because a group of Japanese researchers have used Mycetozoa (single-cell slime moulds) to prove it. They built a model of Tokyo and subsequently placed a single rolled oat in its centre and surrounded it with smaller oats to represent important transport hubs in the city. In search for sustenance, the mould has created a network similar to the one designed by people.

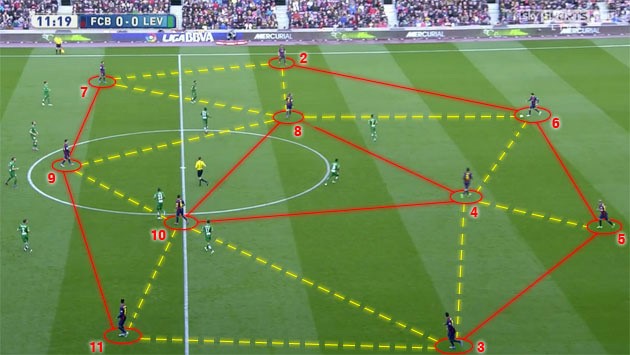

Barcelona triangles

Football teams, just like Mycetozoa, form structures. Eleven players are placed on the pitch in carefully chosen formations. Currently, one of the most popular are the Barcelona triangles. Although they weren’t invented in that city, it was there that their true potential was unlocked.

The formation, first introduced by Spanish football coach Pep Guardiola, allowed the players to quickly pass the ball between themselves. The key to success was to keep a close distance between one another, effectively making it impossible for the opponent to be sure to whom the ball is going to be passed next. As long as they had the initiative, they also had an advantage.

But what happens when the opponent has the ability to disrupt this formation by employing man-to-man defence or pressing (an attempt to recover the ball in the shortest possible time)? Then there comes the time for mathematics. During the 2013 World Cup semi-finals, FC Bayern Munich has shown FC Barcelona that their tactic is a double-edged sword when they crushed the Spanish team 7–0 in a double-legged tie. This wasn’t a coincidence – it was a masterful execution of a brilliant plan.

But what happens when the opponent has the ability to disrupt this formation by employing man-to-man defence or pressing (an attempt to recover the ball in the shortest possible time)? Then there comes the time for mathematics. During the 2013 World Cup semi-finals, FC Bayern Munich has shown FC Barcelona that their tactic is a double-edged sword when they crushed the Spanish team 7–0 in a double-legged tie. This wasn’t a coincidence – it was a masterful execution of a brilliant plan.

Bayern won the match by playing defensively. In offence, one needs to create and use a lot of free space. In defence, it’s the other way around: it’s important to minimalise not only the possibility of a play, but also the space in which it can happen. As of now, one of the best teams to do that is Atlético Madrid.

The tactics they use during a match are not unlike the ones employed by hunting lionesses. Just like in the case of a football match, there’s no real opportunity to communicate during a hunt, as actions sometimes take place in split seconds. Every lioness in the pride knows what she needs to do, where to make an ambush, and how to use the strength of a group. The same goes for football players: they work as one to reach their goal – in other words, they form a structure.

Technology boom and the beauty of football

212,040,000 is the number of parameters generated by just one football match. We’re in possession of massive amounts of information, but we’re not able to process it ourselves. How is it, then, that people are often able to correctly predict the outcome of a match or series?

Why does a won match earn a team three points? Logic dictates that it would be fair to award two points for a win and one point to each team in the case of a tie – and it was like that in the past. However, it became apparent that it was safer to aim for a tie. After the three-point system was introduced, the number of ties has dropped significantly.

David Sumpter points to the concept of the ‘wisdom of the crowd’, presenting an experiment he once organised for his students. He showed them a jar and asked them to guess the number of pieces of candy contained in it without consulting anyone. Students wrote their estimates on pieces of paper. It turned out that although there was a large discrepancy between the answers, their median value (102) was very close to the actual number of pieces of candy in the jar (104).

In 2012, when Zlatan Ibrahimović scored one of the most beautiful goals in his career, the world stood still. The friendly match between Sweden and England became an example of the player’s exceptional skill. Mathematically, it all came down to applying the right amount of force at a particular angle. But if one of those was just a little off, the goal wouldn’t have happened. And since Ibrahimović couldn’t have calculated it in the span of a split second, it’s pretty safe to say that luck played an important role here as well.

One frequently overlooked aspect of football is the ball itself. The official ball of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa was named Jabulani (‘celebrate’ in Zulu). Its designers wanted it to be perfectly round and smooth, so they used 8 thermally bonded three-dimensional panels instead of the usual 32. As it turned out, the ball became much harder to control.

Mathematics can indeed be an effective tool to describe football matches. It may not guarantee us anything when it comes to gambling, but it does allow us to understand more about the sport.

Source: D. Sumpter, Soccermatics: Mathematical Adventures in the Beautiful Game, Bloomsbury Sigma, 2017.

Image: Sports Illustrated

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl