Can our emotional state be influenced by our digestive tract? Is our stomach a source of happiness or aggression? Dr Magdalena Kurnik-Łucka from the JU Chair in Pathophysiology helped us solve this mystery.

Many of us have experienced a certain feeling of ‘tightness’ in our bellies. It usually happens before important events, like exams or meetings. We even have an expression for it: butterflies in the stomach. However, very few people think about the causes of this sensation. Although the ancient medicine tied the stomach to emotions, its place has been taken over by the brain and the heart.

Over 100 million neurons

Along the entire length of the gastrointestinal tract there is a dense network of neurons called the autonomic nervous system. It’s only recently that we have discovered its exact structure and importance to our organisms. As soon as that happened, the term ‘little brain’ came into being. The use of the word ‘brain’ is no coincidence – the autonomic nervous system is composed of over 100 million diverse neurons. Our ‘second brain’ is built of nerve cells identical to those present in our cerebral cortex, the centre of our memory and intelligence. Although it’s autonomous – for instance, it independently decides how much gastric acid needs to be excreted in order to properly digest food – it doesn’t compete with the central nervous system. It reacts to changes in our internal balance and alarms the rest of the organism in case of any threats.

Both nervous systems are incessantly exchanging information via the longest, tenth cranial nerve called the vagus nerve. Surprisingly, this communication is decidedly one-sided: 90% of the nerve impulses travel from the intestines to the brain. In this way, the brain is constantly bombarded with information, but at the same time is relieved of having to ‘manually’ manage every digestive process. As far as research is concerned, investigating the second brain seems particularly promising when it comes to development and treatment of certain diseases. For example, until recently, most scientists were convinced that psychological issues, such as traumatic experiences or depression, may lead to gastrointestinal diseases. However, thanks to Columbia University’s Prof. Michael D. Gershon’s pioneering research, we now know that these relations may also be reversed – our digestive tract may adversely affect our psychological state, and chronic stress may lead to intestinal disorders. More information on the subject can be found in Prof. Gershon’s book, called simply The Second Brain.

There’s still a lot to learn

‘Unfortunately, our knowledge of the structure of the second brain is still very much incomplete’, said Dr Magdalena Kurnik-Łucka from the JU Chair in Pathophysiology. ‘We lack precise information about the interaction and concomitance of neurotransmitters (chemical compounds that transmit signals between cells) in the autonomic nervous system. We’re not exactly sure which types of neurons are the most susceptible to detrimental factors and what substances can be classified as such’, added Dr Kurnik-Łucka, who uses animal tissue as test subject and spends the most time in immunohistochemistry and morphometrics laboratories.

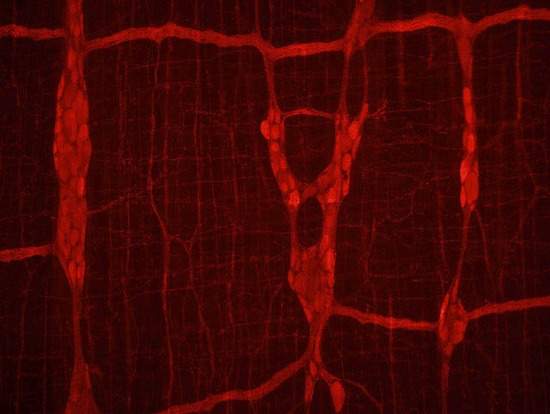

One very useful method of identifying and localising nerve cells is a process called chemical coding, which allows the scientists to discern the aforementioned neurotransmitters. Selected fragments of tissue are dyed using antibodies marked with fluorochromes. Antibody is a type of protein able to recognise antigens (such as neurotransmitters), and fluorochrome is a substance which emits light in certain conditions. This allows the researchers to study tissue under a fluorescent microscope and analyse it using a computer.

Dr Magdalena Kurnik-Łucka conducts research on the influence of neurotoxins on the autonomic nervous system, hoping to gain information which would be useful in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. In the ancient Greek medicine, the digestive tract was considered to be the source of all diseases. Gastrointestinal disorders are one of the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, yet they haven’t been overly emphasised in research papers. Some theorise that these disorders may not be a side effects of the disease, but rather an indication of the important role of the digestive tract in its development. ‘At the Chair in Pathophysiology, we have the equipment that allows us to study these interesting issues. However, like most research projects, it requires time and money’, said Dr Kurnik-Łucka.

Picture under the title: Neurons (green and white) by NICHD Flickr / CC BY

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl