Politicians have always put significant effort into creating their own image. Dr Kamil Kopij from the JU Institute of Archaeology has studied how this goal was pursued by one of the greatest politicians of the Roman Republic: Pompey the Great.

When we look at current politicians as they appear in the mass-media, it seems to us that we know them well. Yet, what we see is only a carefully crafted image. The most important politicians are surrounded by PR specialists, who advise them what should be said in given circumstances and how it should be done. Others rely on their own intuition. There is only one goal: to boost approval ratings.

Propaganda experts claim that the above phenomenon is as old as politics itself. No wonder that political propaganda was common in such an advanced civilization as the ancient Rome. Besides their practical role, Roman monumental buildings, sculptures, and even coins were used as means of propaganda. Caesar, Augustus and Constantine the Great have been known as masters of this art.

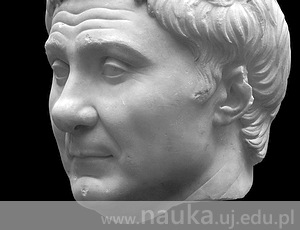

Pompey as Hercules

“Serge Albouy, a French political marketing expert, identified several politician personality types: a hero, an ordinary man, a lover/brother, a father, and an expert. Each of them identifies the dominating features of a politician’s personality in a given moment”, Kamil Kopij explains. “The dominating features may, of course, change over time. Politicians often try to alter their image, according to the changing situation and their own experience.

Hercules – the first incarnation of Pompey. Hercules and Nemean Lion by J. M. Félix Magdalena, licence CC BY-SA

This was precisely the case of Pompey the Great (106-48 BC), whose career was undoubtedly untypical for a Roman politician of his day. Pompey wasn’t born in one of the old republican families whose members had long occupied senior positions in Rome. His father, Pompey Strabo, was the first of Pompey’s relatives to be elected consul. Yet, he died when his son was only 19 years old and was just taking his first steps in the world of politics. We don’t know what Pompey’s fate would have been if not for the conflict between the supporters of the famous general Gaius Marius and Sulla’s faction, which turned from a mere political squabble into a civil war. It is the turmoil of war that enabled Pompey to “make the front pages” without the necessity to slowly climb the formal career ladder. His first military successes earned him the name of a talented commander, but also an “adolescent butcher”, who ruthlessly slaughtered Sulla’s opponents. At the age of about 25 he celebrated his first triumph, which made him one of the youngest Romans to gain this most prestigious award for military achievements.

“His young age combined with military achievements led Pompey to portray himself as the embodiment of Virtus – the divine personification of battlefield courage”, Dr Kopij comments. “By using later terminology, it can be claimed that he portrayed himself as a hero. In contemporary political marketing studies, this term is used metaphorically, but in ancient Rome things looked differently. There are many indications that in the 70s BC Pompey wanted to emphasise his relations to Hercules. Around 70 BC, he probably built, or, what’s more likely, restored one of the temples of this demigod – the temple of Hercules Victor.”

Pompey as Alexander the Great

In the 70s and 60s BC Pompey tried to use every opportunity to strengthen his image of a capable commander. “It can be said that according to Albouy’s classification he became an “expert”. As a matter of fact, the general’s “scientia rei militaris”, that is, expertise in warfare, was praised by Cicero himself in one of his speeches”, says Dr Kopij.

In this period, Pompey was leading legions in Spain. On his way back to Rome, he helped to crush the famous Spartacus’ uprising, and then, after celebrating his second triumph, he managed to curb the scourge of piracy in the Mediterranean and defeated king of Pontus Mithridates VI, who had posed a threat to Roman interests in the Greek east for several dozen years. The latter military expedition reached much further than the kingdom of Pontus. Pompey’s army reached Caucasus, where no Roman soldier had ever set foot before, and then Syria and Palestine, putting a definite end to the Seleucid state and establishing the Roman province of Syria. “Pompey’s eastern expedition became one of the turning points in his image building activities. During the campaign, he started to refer to Alexander the Great and portray himself as his Roman successor. This shift was likely to be influenced by Theophanes of Mytilene, Pompey’s trusted companion who wrote a book about the general’s expedition to the east, which did not survived to the present day, but surely served as a source for many later authors. Theophanes himself may be considered one of Pompey’s “spin doctors”, adds the archaeologist.

After coming back to Rome, Pompey was not only one of the most powerful, but also one of the richest Romans. His third triumph in September 61 BC lasted for two days, and Pompey became the first Roman to be honoured in that way for victories won on three different continents: Africa, Europe and Asia. This fact is illustrated by coins which are linked to Pompey, although it wasn’t him who minted them. They show three tropaions (symbols of victory in the form of a pole hung with armour) or wraths, which can be seen on coins minted by Faustus Sulla, Pompey’s son in law.

Pompey as a Companion to Victorious Venus

In the 50s BC, Pompey’s image started to evolve from a hero and expert to a father. Pompey hoped that the prestige gained in the previous decades (the Roman dignitas) would allow him to exert decisive influence on the Roman politics without introducing any changes in the governmental system. “However, the Roman politics was hard and this was clearly a miscalculation. This led to one of the most fascinating political alliances in history - the first triumvirate, made by Pompey, Caesar and Crassus.” The three headed monster, as referred to by Varro in his satire Trikaronos, pursued its goals with varying degree of success. The triumvirate usually managed to secure the support of the Senate or the Plebeian Assembly, but the price its members had to pay for achieving their objectives was the rise in political violence, stemming from the use of methods that would today be called unconstitutional. Yet, this didn’t stop Pompey from portraying himself as princeps senatus – the first senator, who was a sort of father figure, as this role was usually performed by the oldest and most experienced senator.

“The buildings funded by Pompey in Rome included the temple of Venus Victorious”, adds Dr Kopij, “and Venus was considered the first mother of the Romans. No wonder why the politician who wanted to be perceived as a father chose this goddess.” The post he occupied undoubtedly helped him create this image. For several years, he was responsible for supplying Rome with grain. As he did that very effectively, he earned the gratitude of the Roman people. In 55 BC he was a consul together with Marcus Crassus. Three years later – in the face of a giant political turmoil – he was chosen consul without colleague (Latin: “consul sine collega”), which means he held this position alone, although according to the law there always had to be two consuls (if one died while in office, he was replaced by a newly elected official).

“Pompey wanted to put into practice the model of princeps senatus known from Cicero’s writings (such as the treaty On the Commonwealth and, referring to Pompey himself, in the speech On the Command of Gnaeus Pompey) and consistently promoted this model as part of his own image. His defeat in civil war against Caesar at Farsalos on 9 August 48 BC and the subsequent death off the coast of Egypt ruined his plans to dominate the Roman politics. A similar way was later taken, this time successfully, by the first Roman emperor, Augustus”, Dr Kopij concludes.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl