Fever is one of the key defensive mechanisms our organisms use to combat diseases. What’s interesting is that it’s not only found in warm-blooded animals (such as mammals), but in cold-blooded ones as well. In the latter case, it’s called the ‘behavioural fever’.

In collaboration with Prof. Alain Vanderplascchen’s research team from the University of Liège (Belgium), Dr Krzysztof Rakus from the JU Institute of Zoology Department of Evolutionary Immunology conducted a study on behavioural fever in fish. The results of his research was published in the Cell Host & Microbe journal (Impact Factor: 12.552).

Behavioural fever

Fever, or an increase in body temperature, is one of the symptoms of inflammation, i.e. the organism’s complex defensive response to bacterial or viral infection. When a pathogen enters our body, immune system cells (leukocytes) produce substances that stimulate the organism to fight it. Some of the substances, such as cytokines (proteins regulating the activities of cells fighting the infection) are responsible for inducting the fever. One example of cytokines is tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). This type of cytokine is found in all kinds of animals, like mammals or fish.

Fever, or an increase in body temperature, is one of the symptoms of inflammation, i.e. the organism’s complex defensive response to bacterial or viral infection. When a pathogen enters our body, immune system cells (leukocytes) produce substances that stimulate the organism to fight it. Some of the substances, such as cytokines (proteins regulating the activities of cells fighting the infection) are responsible for inducting the fever. One example of cytokines is tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). This type of cytokine is found in all kinds of animals, like mammals or fish.

Fish are cold-blooded, and in most cases, their body temperature is close to the temperature of the water they live in. Similarly to other poikilotherms (cold-blooded animals) – reptiles and amphibians – fish migrate to warmer places when they’re infected with a pathogen. This phenomenon is what we call behavioural fever, since it leads to an increase in an animal’s body temperature caused by its behaviour. Raised temperature allows for more effective defensive measures and reduces the rate of pathogen multiplication. Although fever is very important in fighting diseases, as evidenced by the evolutionary path of vertebrates, until recently we’ve had very limited knowledge as to what causes behavioural fever in fish.

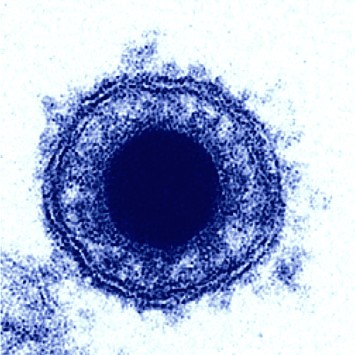

When conducting their research, Dr Krzysztof Rakus and Prof. Alain Vanderplasschen studied carps infected with the CyHV-3 virus (cyprinid herpesvirus 3). Since the early 1990s, this virus, also known as KHV (koi herpesvirus), was responsible for mass fish deaths worldwide. The virus can reproduce between the temperatures of 18°C and 28°C, but is unable to multiply when the temperature rises to 30°C.

‘Our research shows that when the fish are able to freely move around between aquaria with different temperatures, they migrate to the ones with higher temperatures in order to stop the infection. We discovered that the healthy carps preferred to swim in colder water (24°C), while the infected ones chose a warmer environment (32°C)’, explained Dr Krzysztof Rakus. Because of this, all of the fish survived the infection, which would be next to impossible if the water temperature was 24°C everywhere.

Virus modifies the host's behaviour

During their study of the behavioural fever, the researchers noted that infected carps were very late to move to the 32°C section of their aquaria. They did so when nearly all symptoms of the diseases could already be observed. In other words, the fish were already very sick when the decided to move to a warmer place.

So could the virus be responsible for hampering behavioural fever? If so, how? The scientists took a closer look at the virus’ genome to find the answer. It turned out that it contains the ORF12 gene, which, putting it simply, regulates the production of a viral protein that ‘traps’ the carps’ TNFα. The researchers then genetically modified the CyHV-3 virus by removing the ORF12 gene. Carps infected by the modified version of the virus were a lot faster to migrate. The virus’ influence on its host became obvious.

‘To prove beyond doubt that it’s the TNFα that's causing behavioural fever in carps, we injected the fish with antibodies which block this type of cytokine. The fish completely stopped migrating to warmer waters. The mortality rate increased severely’, said Dr Rakus.

The research published in Cell Host and Microbe not only points to evolutionary mechanisms of fever development in fish and mammals, but also for the first time describes how a virus can modify the host’s behaviour by producing a single protein. It’s a very important ability for the virus, since it takes a longer time for the infected fish to seek warmth, allowing for more effective reproduction and spreading of the virus.

Dr Krzysztof Rakus works at the JU Institute of Zoology Department of Evolutionary Immunology. He is a comparative immunologist. He specialises in fish innate immunity against viruses. Currently, he leads the research project DExD/H-box rna helicases in fish antiviral response within the framework of Sonata Bis 5 programme.

Photographs: Dr Krzysztof Rakus.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl